Magellan’s Landing Site: The Harbor of Butuanon Pride and Pretense

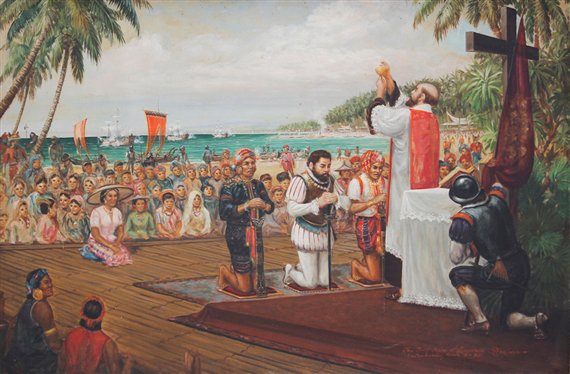

On the 31st day of March, every year, the city of Butuan celebrates ‘’Mazaua Discovery Day’’ to commemorate a historic milestone, the 1st Easter mass on Philippine soil celebrated by Ferdinand Magellan on March 31, 1521. For three centuries of almost uninterrupted tradition, notably the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, the celebration persists. The topic of the first Philippine mass has stirred a debate for hundreds of years; however, no matter what, Butuanons proclaim with pride that such a historic event took place in Butuan, not in Limasawa.

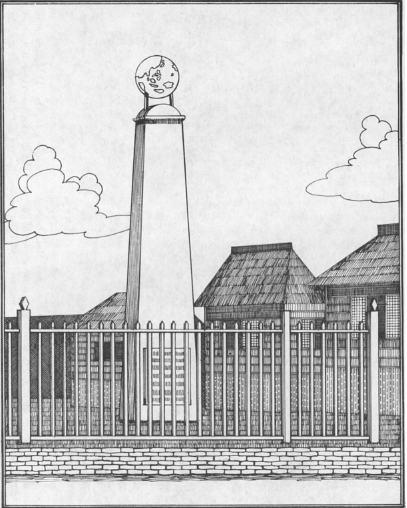

The monument, in complement with the Bood Promontory 1st Easter Mass Eco Park, was constructed to commemorate the landing of Magellan as well as the First Mass in this place on April 8, 1521. However, in 1953 another monument was placed on the island of Limasawa, which challenged the centuries-old “unchallenged conviction”. This report investigates the geographical, historical, and political context surrounding its construction, how it connects the past, present, and future Butuan, and how its current situation puts Magellan’s Landing Site at risk of demolition.

About Magellan’s Landing Site

The Magellan’s Landing Site was built in 1872 under the district governor Jose Ma. Carvallo. Located in Brgy. Masao Butuan City, Agusan Del Norte, this site is believed to be where Magellan landed and made a blood compact with Raja Siaiu. At the mount of Masao River, the Magellan’s anchorage stands, as it is a location claimed to be Magellan’s landing site in the Philippines. Apparently, the monument was erected at the instigation of the parish priest of Butuan, who at that time was a Spanish friar of the Order of Augustinian Recollects.

Now it has been sited at Barangay Masao, near the entrance to the Masao River. The monument is said to have been built to commemorate the historical event of Magellan’s Landing on Philippine soil. However, this is a known topic of controversy since several historians claim that Magellan’s expedition never reached Masao. In contrast, others argue that, indeed, Magellan and his crew first landed in Masao.

On the position paper of the Butuan Historical Commission, history has this to say: Antonio Pigafetta and the Official Chronicler of Magellan’s fleet wrote,

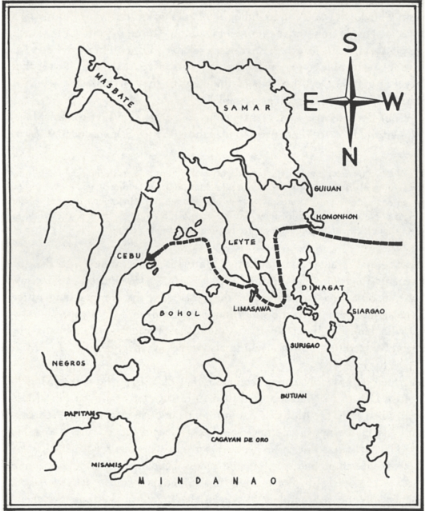

“…as we have seen a fire on an island (Masawa) that night before, we anchored near it.”

Butuan Historical Commission claimed that the bright light was the beacon in the darkness that guided Magellan’s fleet to the isle. “Masawa” means “bright” in Butuanon, the only language in the Philippines that contains the word. However, historians widely believe that Limasawa, off the tip of Southern Leyte, is the place where Magellan’s Landing was made.

During that time, Mazzaua (Masao) and Butuan were ruled by a Manobo Chieftains – Rajah Siago and Raja Calambu (Raia Calambu and Raia Siani). The food that was served to the guests explicitly identifies that the Masao and Butuan rulers were eating (pig flesh) or pork. And since, during this time, there was no proof of Christianity, it would be certain that the people in Masao and Butuan were believers but not of Islam. Addtionally, Raia Calambu and Raia Siani were habitually chewing areca nut. The betel nut is obtained from the palms found in the forest. In the writing of Pigafetta, there was no mention about the Areca betel nut and about the people who were chewing while they were in Ladrone islands, Zamal and Humunu. This implies that no one in the previous islands had been seen by Pigafetta chewing and only in the new islands, Masao and Butuan.

The presence of gold mines, too, is an evident indicator that the first Easter mass happened in Butuan City as the king of Zuluan (Butuan) and Calagan (Surigao) have gold mines in their place and the people possesses gold which they made for their adornment. There was no mention of gold in Limasawa, much more about gold mining activities in the island. Moreover, the excavation of Balanghai in as mentioned in the chronicle of Pigafetta had been affirmed that there existed a long boat, balanghai, through the discovery of buried balanghais in Brgy. Libertad, near Masao, Butuan City which has not been found in Limasawa. The houses in Masao has a 1 meter to 8 meters distance above the ground. This is very common to a flood prone areas. Masao and Butuan have at least three rivers; Masao River, Agusan Pequeno River and the great Agusan river. To elevate the flooring of the house is not needed in Limasawa since has no river that may cause flood when it overflows instead the houses there are built low due to the frequent typhoon.

Surrounding the monument are multiple structures. On the north side of the monument, there are numerous “Sari-sari” stores selling food such as chips, beverages, as well as fish, and pork meat, if people want to grill. Behind those stalls is a covered court where locals would play basketball or volleyball on a daily basis. Because the monument is near the beach, on the east and west part of the monument are cottages for people to rent and a “Liempo Masters” stall for people wanting to buy liempo and lechon manok. Lastly, on the south side of the monument is the beach where people gather and have fun.

The place is quite remote from the main highway. To get to the monument in Masao, a person needs to go to Brgy. Libertad first. There you can find many tricycle drivers, motorcyclists, multicabs, and taxis that would be happy to take you to the monument at a reasonable price (around Php 15 for a one-way trip).

Voyager of Timelines: MLS Uniting History and Modern Society

For locals, the essence of Magellan’s Landing Site has grown beyond mere appreciation for the first circumnavigator’s arrival in Butuan City. It has become a relic of solidarity, patriotism, and the value of history – all historical testaments for Butuanons to be proud of their homeland. This monument also serves as a commemoration of the warm and enduring hospitality of the locals, the genuine heritage and vintage identity woven in the place. As the United Nations, before there was the Philippines, there was already Butuan. Indeed, the monument is the culmination of 250 years of Butuanon culture and has been celebrated year after year.

“…before there was the Philippines, there was already Butuan.“

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

This Magellan’s Landing Site has significant ties with great historical and religious events such as the First Mass of the past, hence why the landing site has become the basking site of reflected glory. The Easter Sunday mass of 1521 was an imagined treasure that Butuanons have claimed up to this day. The event was engraved so deeply into the culture that they have built the said monument, along with the Bood Tree Park, as a replica of their flesh, blood, and heart. With a heavily Christian nation, the prestige of having their hometown be the location of the First Mass is something to boast about to all.

Moreover, as the City of Butuan strives to achieve a vision of a great, inspirational, competitive, liveable and sustainable city, this historic site acclaimed by Butuanons represents their will to make Butuan a world-class hub of opportunities for all that spurs. The region may have suffered a significant decrease in production noted in various industries. Despite the economic setbacks brought upon by the pandemic and natural calamities that hit the region, a trend of increase during the last quarter of 2021 was observed. In fact, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority, 22,442 businesses have been established by the region since the last quarter 2021 and with the 2021 Regional share to total exports, the Caraga Region’s growth reached to 84.39%. This year, the Caraga region is aiming to be the Fishery, Agro-forestry, Mineral and Eco-tourism (FAME) Center of the Philippines. The Magellan’s Landing Site, being at the heart of a progressive community of farmers, fishermen and wayfarers, continues to cultivate a culture of competitiveness, in turn significantly bolstering Caraga Region’s sustainable growth and development.

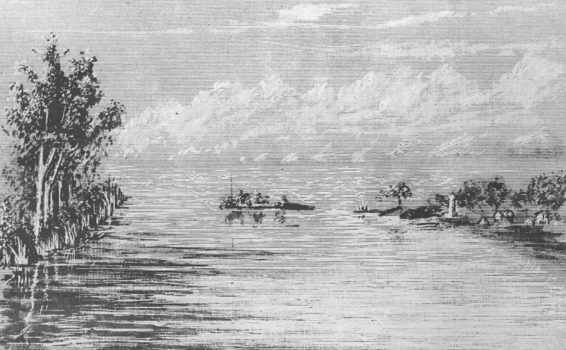

Today, the Masao River at Brgy. Masao, the barangay where this monument stands firm, continuously rakes in tourists within and outside Butuan. Although it is falling behind compared to the monthly revenues and average influx of tourists on other beaches within the city, Masao remains a budget-friendly hangout destination where people can unload barrels of laughs or blow away the cobwebs. The construction of Magellan’s Landing Site, right at the entry of the coast, would serve as a constant reminder to travelers that this place is more than deserving of respect, as it once harbored one of the most influential contributors to Philippine and world history.

One problem though: it did not.

A Tell-Tale Tragedy: MLS as an Embodiment of a Lost Cause

For two and a half centuries, the claim that Magellan have went to Masao and performed the first Catholic mass in the Philippine Soil reverberated to the locals, fueled by a misconception that documents written during the Spanish period are considered primary sources because they are basically Spanish. Some of the Butuan proponents, especially the Butuan Historical Commission argued that the following Spanish sources mention Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass are valid sources:

-1581 edict of Bishop Domingo Salazar in the Anales ecclesiasticos de Filipinas 1574-1683;

-the 1886 Breve reseña de diocesis de Cebu;

-Fr. Francisco Colin’s Labor evangélica: Ministerios apostolicos de los obreros de la Compaña de Jesus (1663);

-Fr. Francisco Combés’ Historia de Mindanao y Jolo (1667);

-Fray Gaspar de San Agustin’s Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1698);

-the 1872 monument in Magallanes, Agusan del Norte; and several more accounts written by American authors in the early part of the 20th century.

However, all of these sources were invalidated when scholars gained complete access to one of the four extant manuscripts of Pigafetta’s chronicle of the Magellan-Elcano expedition in 1800: the Italian text archived in the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, Italy, which mentions nothing about Butuan as the site of the 1521 Easter Sunday Mass but Mazaua. It had explicitly stated that on Easter Day, 1521, Herrera, the Cronista Mayor of the Royal Court of Spain, a Mass was celebrated and a Cross was erected on a promontory, at a little island called Mazagua, which is now known as Limasawa.

To end the conflict for the issue of the first mass, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) panel adopted the recommendation and unanimously agreed that the evidence and arguments presented by the pro-Butuan advocates were not sufficient and convincing enough to warrant the repeal or reversal of the ruling on the case by the National Historical Institute (the NHCP’s forerunner). With this, the academic community agreed to a settlement that the island of Limasawa was the first one baptized by Christianism, and that the Spaniards never traversed the city of Butuan during their first circumnavigation of the globe.

Allowing Magellan’s Landing Point to remain standing would tolerate toxicity among Butuanons that would never falter in realizing the truth. Even the people of Manila will never fully understand how tenacious the people of the Butuan Historical Commission are – How in just 250 years of a peculiar event, the First Mass has become the flesh, blood, and heart of the people there are. The first mass tradition of Butuan did not start with the Historical Commission of Butuan. The latter defended the tradition only after historians had determined that the First Mass was in Limasawa. Such historians made the Butuan Historical Commission angry since they were essentially removing the glory of Butuanons. Also, perhaps because how long the tradition has been believed that no matter the evidence, they would never heed to the promptings of others. Now that the academe had collaborated for a unified judgment, Butuanons have to accept the fact that Magellan may have not set foot on their land at all, and destroy the monument that gave them a false sense of patriotism.

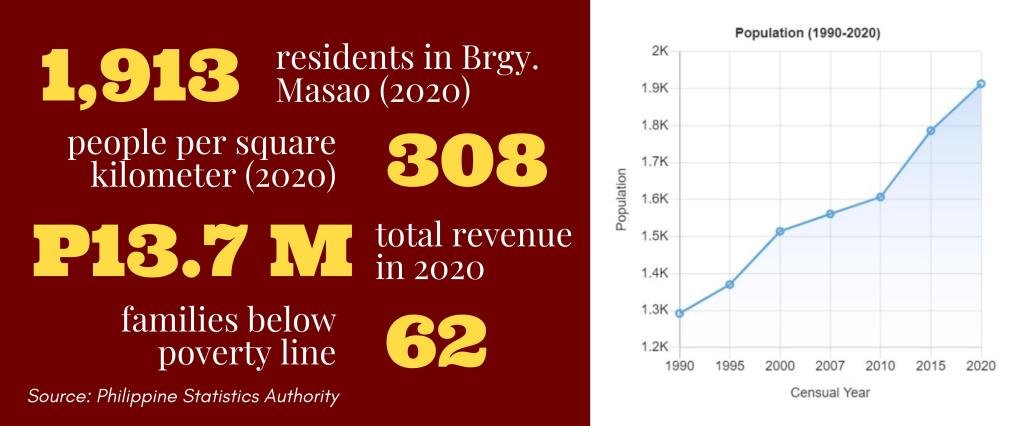

Locals have also raised concerns on the narrowing land resources which may compromise families living below the poverty line. As a barangay in the independent city of Butuan, Brgy. Masao experiences a constant population growth; during the 2020 Census by the Philippine Statistics Authority, there were 1,913 residents. Though this represented 0.51% of the total population of Butuan, the barangay occupies much smaller land area at about 6.21 square kilometers. Meanwhile, The household population of Masao in the 2015 Census was 1,786 broken down into 359 households or an average of 4.99 members per household.

The population of Masao grew from 1,292 in 1990 to 1,913 in 2020, an increase of 621 people over the course of 30 years. The latest census figures in 2020 denote a positive growth rate of 1.46%, or an increase of 127 people, from the previous population of 1,786 in 2015.

The roughly 50 square meters spacious area used in building the monument could be used to inhabit Butuanons below the poverty line. In fact, the back wall of the monument has been used as a support for a small hut where a local uses it as a storage. Instead of having a monument lacking in historical accuracy and maintenance, the spacious area could be used to build much more valuable structures such as a residential area or commercial establishments.

The two major reasons may have contributed to the pitiful present of the faux relic: the once majestic site is now on the verge of falling apart at the seams. The monument honoring Magellan’s Anchorage–as claimed by Butuanons–has not been adequately maintained. There has been much graffiti done to the monument, and the statues have parts where it has deteriorated. Obvious peeling paints and algae growth can be observed. It would be a fantastic feat if the statues would even last another decade or so.

The monument is situated next to a typical beach with cramped local stores around. It’s out of the way and hard to find – old and falling apart. Somehow, the site’s been concealed with the amount of infrastructures that’s been surrounding it. It is not attention-grabbing anymore, far from what it used to be before. Moreover, there is not much to do other than take photographs of the monument since no information is available. As a result, it is only worth looking into because of its so-called historical significance.

As citizens of the Philippines, we must be aware of the reality behind different stories written in our history. Lies must not blind us, and we must learn to live with them, just like with Magellan’s Landing Site representing the first arrival of Magellan and his crew on Philippine soil. Many Butuanons might find it easier to believe what the majority of Butuanons say about how the first mass and Magellan’s arrival happened in Masao, Butuan City. However, it has been proven by many historians that that is not the case, also taking note of the fact that pro-Butuan advocates did not have enough evidence to prove their stand on the controversial topic. With this, we can say that if only people could find it in themselves to try and learn the truth about their history, it would make way for clarity and peace to prevail.

In order to achieve one of the primary goals of Butuan City to have growth and development as a city, specific actions must be taken. Having a monument that stands as a representation of something that could not have even happened would be an obstacle to achieving the so-called progress expected by the city. To overcome this obstacle, people must find ways to eliminate the “problem,” maybe through demolition or any means of removal. Only through this way can the Butuanons and the rest of the pro-Butuan advocates finally move on and move forward.

Lies must not blind us,

and we must learn

to live with them.

Authors

Adlaon, Rovi Fe

First Year Student,

BS Biology (Microbiology)

MSU-IIT

Bustillo, Elsa Mae

First Year Student,

BS Biology (Microbiology)

MSU-IIT

Pag-ong, Ski Vinray

First Year Student,

BS Biology (Microbiology)

MSU-IIT

Restor, Jonathan Jr. R.

First Year Student,

BS Biology (Microbiology)

MSU-IIT